Esther Freud's Ode To The Magic Of Hampstead's Ladies' Pond

Getty Images

Aged 16, and newly moved to London, I had no idea that Hampstead Heath existed – it was nightclubs, theatres, the smoking carriages on the tube that most excited me – but all the same I couldn’t pretend to be unmoved by such a tract of nature. The trees, hills and wildflowers were so much more luxurious than the neat fields and golf courses of East Sussex, and then, to discover, hidden down a leafy lane, behind a scrub of saplings, a secluded lake for the use of women only. No men, children, radios, dogs – the sign on the gate warned, and as I walked down the path beside the sloping meadow, and stood on the wooden deck above the mud brown pond, I had the unusual sense that I was exquisitely lucky to be female.

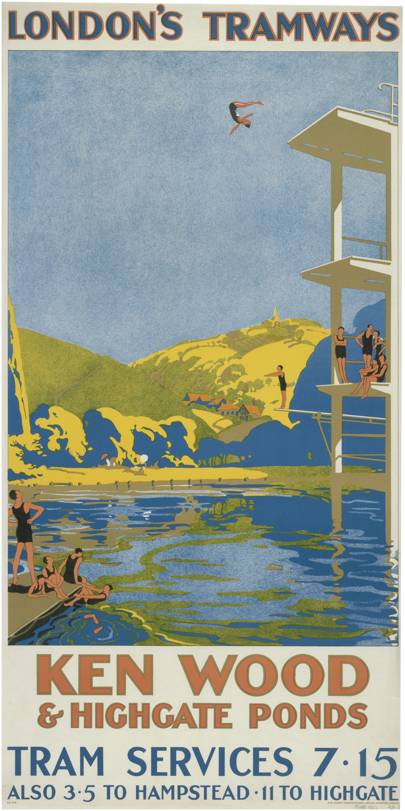

There are numerous ponds on Hampstead Heath, as many as 30, but only three are reserved for swimming – a mixed, a men’s, and the Kenwood Ladies‘ Pond, which was officially opened in 1925, although women had been using it for centuries. There used to be night swimming by candlelight (now people make use of the dark to climb over the fence), and Katharine Hepburn once visited and brought a tin of biscuits for the lifeguards to have with their tea.

Today there is a group of year-round swimmers who come daily, through hail or frost, and dip themselves into the water. There are long winter months when it is only them. And then, at the height of summer, as many as 2,000 women, of every shape and size, all classes, all ages, from across London, across the country, even from abroad, arrive to swim and sunbathe on the meadow. And the meadow is as important as the pond itself. It is a magical place, entirely private – topless sunbathing has been allowed since 1976 – and once you lie back on your towel all you can see are trees and sky. There is so much space here. So much peace. And above the birdsong the only sound is the hum of chat and laughter and the occasional scream of someone new braving the cold. You can lie in this meadow until dusk, because you’ve paid your dues, you’ve already immersed yourself in the deep, dark lake, and for now at least you don’t have to go in again.

Getty Images

Dive Into The Most Beautiful Wild Swimming Spots In The UK

For many years I was a fair-weather swimmer, circling the pond just once on the sunniest of days, congratulating myself as I climbed out. But then, one autumn, after a difficult summer, when, increasingly, a swim was the only thing that raised my spirits, I decided to keep going. I arrived, fragile and fearful, on a cold, damp Sunday morning, early, to meet a friend who’d swum through the previous year, and ignoring the temperature scrawled on the board (14C) I took courage and followed her down the ladder. It’s so cold! My body screamed as I struck out for the far end, anxious thoughts pursuing me, self-pityand resentment dogging my every stroke. Why am I even doing this? What if I have a heart attack and die? Two ducks glided by, and a heron, wise and faintly disapproving, watched me from the bank. I dipped my head under and, just like that, the mud silk of the water soothed me, released me, and when I burst up, I felt, for a moment, happy.

The next Sunday was already easier. It was a bright, crisp day and cheered by my courage in returning, I swam round twice and when I came out my body was blazing. I stood in the sunshine and chatted excitably, no need even for a towel, but within 10 minutes I began to shake. The cold was like a burn: it had bedded so deep inside me I wasn’t sure I’d have the strength to drag my clothes on, heave my arms into my coat. Speechless, I found my way back to the car, drove the mercifully short distance home and stood in the shower until I was warm. Later I confided in my swimming friend, and she told me I should have asked for a hug. Body heat is the best cure for hypothermia. And she advised me to invest in neoprene gloves and socks. The following week we met on the other side of the Heath and walked fast before we swam. Already warm, it was easier to get in, and harder to get out, and afterwards, although I was still shockingly cold, I arrived home tingling and ravenous, for food, for fun.

By mid-October half the pond was cordoned off. The lifeguards issued warnings. This is proper winter swimming now. You need to come twice a week at least to acclimatise to the temperature as it plummets. Don’t stay in too long. Enjoy. And don’t forget to breathe. By now most of the women were wearing bobble hats, fluorescent pink and yellow, the better to be seen in the early morning murk. But I resisted, savouring the shock of bliss as I cleared my head with a dip under the water. It released my worries. Put me in the moment. And the moment, just for a moment, was good.

On the winter equinox there was a party. Breakfast was provided, croissants, berries and tea, and the pond was hung with lanterns. As many as 50 women climbed down the ladders, struck out across the silvery lake as the sun rose above the trees. By now I was familiar with the changing room regulars – mothers who managed a quick dip after dropping off their children, women on their way to work, octogenarians who revolved in their own circle. “See you tomorrow,” they waved merrily as they bundled off into their day. I loved being surrounded by so many women, all naked, all happy to be so as they jostled for space. It was ridiculous and oddly sexy. And a whole new etiquette had to be mastered in order to greet an acquaintance wearing only a neoprene sock.

Getty Images

Four Places To Swim Outdoors In London

That winter, on holiday on the Suffolk coast, I joined the Christmas Day swim. For years I’d marvelled at the insanity of anyone prepared to strip off in public in December, but this year I threw myself into the waves. By the time I came out I’d been swept so far from my starting point by the current, I had to search, my skin scorched red, through the crowd to find my clothes. But nothing mattered. I was insulated. Deep inside.

And then, in the New Year, it snowed. Now what? I texted. Surely we can stay in bed today? But I was a year-round swimmer and there was no backing down. The pond was almost entirely frozen over. There was one narrow lane where the lifeguards had broken up the ice with an oar, and there were three bobble-hatted women doing lengths. I climbed down the ladder and felt the cold cut up between my legs. It flayed my arms, cracked my skull. “I feel good,” I used my breath to sing a snatch of James Brown, and as I plunged under I felt the water bubble round me, as refreshing as champagne.

Swimming in cold water, I read afterwards in an article pinned to the changing-room wall, raises your white blood cell count and your libido. The best way to get warm is to put your wrists in hot water. I’d come to love this changing room. A small fuggy outhouse with one hot shower and a tap, several plastic basins, rubber mats and wall hooks, it was due to be dismantled during my first winter to make room for a larger, smarter version, and while the work was being carried out the Ladies’ Pond was to close. Here was my chance to stop my swimming challenge and re-start in the spring (I’d got to February after all), but the Ladies’ Pond was re-allocated to the Mixed Pond, and on the weekends we were given access to the Men’s. I’d never thought much of the other ponds. I was utterly loyal to my own, and had taken a condescending approach. You’ve no idea, I’d often thought as I walked past. But I found myself delighted by the leafy safety of the Mixed, and the wide expanse of the Men’s, with no changing room or shower, was Spartan and surprisingly jolly. “Everything today will be easier after this,” I said one particularly bracing morning. And a man waiting by the diving board grinned. “Everything in life.”

Getty Images

In early May, the Ladies’ Pond re-opened and we all flooded back. The changing room had a slick, Swedish feel and although there was some disgruntlement (was this building designed by a man?), the beloved ingredients remained. There was still, mostly, only one hot shower, and there were the familiar plastic basins which women used to splash themselves, or stood in to thaw their feet.

There was an opening party, with croissants and berries, and when we swam the water was still cold from the icy months before. But soon the rewards began. From two degrees to three. From seven to eight, up to 10. Then 12, and when it reached 14 it seemed so warm I was surprised I’d even shivered. One day the temperature reached 23, and by midsummer I was positively looking forward to the cold shocks of my second winter, the release of adrenaline, the warmth of the deepened friendships, because to swim in the Ladies’ Pond at any time of year is like being part of an exclusive club. There is a special bond between the women – they smile at each other as they glide by, and introduce their daughters to the lifeguards as they come of age. Girls have to be eight to swim, and when they arrive they are watched over as they take their first strokes. Now, each time I walk down the shaded path, I think of the friends I’ve swum with over 30 years, the new friends I’ve made more recently. When we meet, we laugh and congratulate ourselves and remind each other to wipe the mud beards off our chins. And we need to be reminded because when you rise up out of the velvety water you feel so powerfully beautiful that it’s possible to forget to look into a mirror for the rest of the day.

It’s well known that swimming in cold water has physical benefits, but there are others that are harder to define. Swimming past waterlilies and nesting ducks, breathing in the watermelon scent of the mud, sailing in slow breaststroke past weeping willows. It is all so different from the pounding lengths of a traditional pool, where it is possible to drag your worries with you from one end to the other. Here, my sense of myself was altered, the cold too shocking to focus on sorrow and confusion when the useful thing was courage, and when my heart had steadied, and I realised I was not actually going to die, the exhilaration hit me and I felt dizzyingly grateful to be alive.

At The Pond, a collection of essays by different authors about swimming at the Hampstead Ladies’ Pond, will be published by Daunt Books on 20 June, priced at £9.99

0 Коментарии